It’s an odd thing to buy: a doll that belonged to a dissident in Ceaușescu’s Romania. Doina Cornea used dolls similar to this one to send letters critical of the regime out of the country, for broadcast by Radio Free Europe. One of them played a prominent role in Roumanie: le désastre rouge, a documentary made in 1988 by Josy Dubié and Jean-Jacques Péché, which dramatically changed the way the Romania was seen in the west.

This particular doll, however, appears to have stayed at home; an understudy, a bystander in the closing days of Romania’s dictatorship. And yet someone did buy it, for €700, at an auction last week in Bucharest. It was among 28 lots put up by Cornea’s estate to fund a foundation that will celebrate her life and work, and promote the values for which she campaigned.

Doina Cornea’s doll, auctioned in Bucharest, December 2020

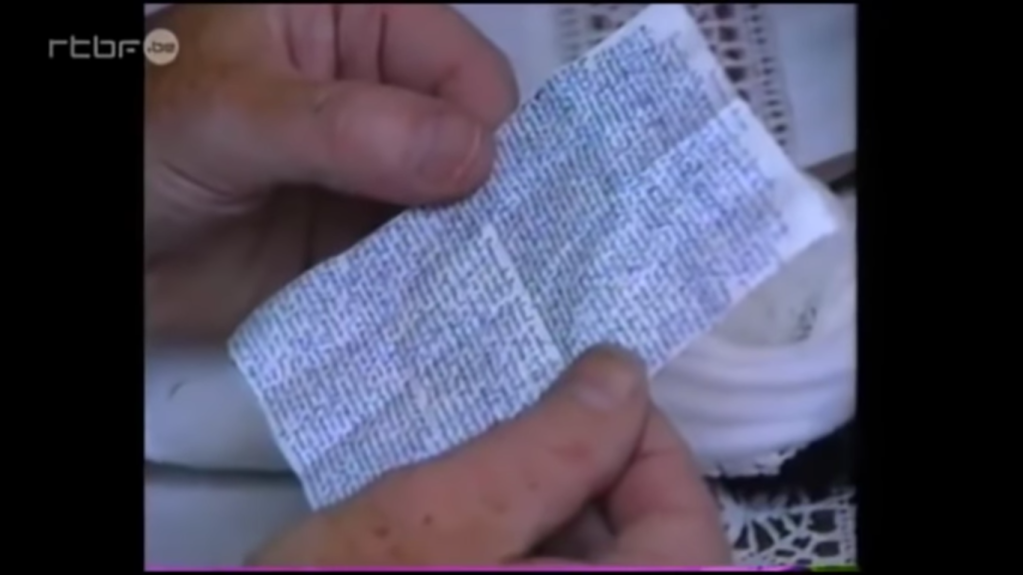

The auction documents do not exactly say that this doll missed its destiny, but reading between the lines this seems to be the case. It was one of three dolls, the catalogue says, bought to smuggle letters out of the country. Interviewed in 1993 for the short film Păpușa, by Marius Șopterean, Cornea recalled selecting the dolls and described how she was able to slip the tiny letters between the fabric of the doll’s hood and its plastic face.

The first doll left with Dubié in the summer of 1988, containing two letters. One was an open letter to Ceaușescu, criticising his rule and demanding reforms; the other a letter to be read to a conference organised by the Polish Solidarity movement in Cracow. The story goes that Cornea saw Dubié’s car, conspicuous by its Belgian number plates, close to the church she attended in Cluj, and quickly asked the foreigners to take the doll with them. After checking who she was with the Belgian Embassy in Bucharest, Dubié returned to Cluj and succeeded in getting past her minders to film a brief interview.

In Roumanie: le désastre rouge the doll is shown sitting on the back seat of Dubié’s car, as if left by a careless child. This is followed by a scene where the doll is cut open. Two letters, tightly folded squares of paper covered in miniscule handwriting, are extracted from the stuffing in its head. The doll is also shown in the studio of Radio Free Europe, present as one of the letters is broadcast. And later it is handed to Mihnea Berindei, of the Paris-based League for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania, to whom one of the letters was directed.

Emil Hurezeanu, formerly a journalist with Radio Free Europe in Munich and a participant in the film, later recalled Dubié arriving at the station to deliver the letters, and the impact the film had once broadcast in December 1988. “After Désastre rouge, Romania suddenly went from being a forgotten country in the south-east of European, or at best one known for its non-conformist relationship with Moscow, to being seen for what it was: a country sacrificed, along with its unhappy people, at the whim of the national communist dictatorship.”

A wave of international protest and solidarity followed, with campaigns launched to address specific issues brought to light by Cornea’s letters. For example, Opération Villages Roumains was set up in Brussels to campaign against the systematic destruction of rural communities by twinning them with Belgian villages. Cornea, meanwhile, was placed under house arrest.

The second doll, containing a letter addressed to Pope John Paul II, left the country with Cornea’s daughter, or more precisely in the arms of her 10-month-old granddaughter. This doll was later donated to the Sighet Memorial Museum to the Victims of Communism and to the Resistance.

This leaves the third doll, which presumably Cornea kept for sentimental reasons or for future use. And you never know, there might even be a letter inside it. I wonder if the person who bought it will risk damaging their investment to find out.

text © Ian Mundell 2020