Often it takes the death of a filmmaker to get their films out of the archives and onto the screen. So it is with Robbe De Hert, who died in August at the age of 77. Long celebrated as the enfant terrible of Flemish Cinema, it is finally possible to see where some of that reputation comes from, thanks to memorial programmes this month in Ghent and Antwerp.

But these isolated events — all the more transient at a time when it is hard to get to the cinema — need to be followed by an effort to make his films available on digital platforms or DVD. If he is so important to the development of Flemish cinema, as the obituaries all say, it would be good to see why.

De Hert’s importance primarily lies in Fugitive Cinema, a collective he helped set up in Antwerp in the mid-1960s. Inspired by the Free Cinema movement in the UK, it made socially engaged and experimental films, mixing documentary, drama, collage and animation. It was particularly influential for its ‘off-television’ productions, reportage on social issues that the public television refused to address.

SOS Fonske (1968), for example, showed a family going through the humiliation seeing its belongings auctioned on the street to cover the cost of a bankruptcy. Rather like the early work of Ken Loach, it helped launch reforming legislation. Meanwhile Dood van een Sandwichman (1971) looked at the way commercial and political interests took over the funeral of a young cyclist.

De Hert collaborated on these films with Guido Henderickx and Patrick Le Bon, who would also go on to careers as feature directors. Meanwhile De Hert made his own films, such as De Bom (1969), a short about a garage owner who finds a lost American atom bomb in his garden, and Camera Sutra (1973), a sprawling broadside against Belgian society.

In the 1980s De Hert’s career took a surprisingly commercial turn, beginning with the historical drama De Witte van Sichem (1980), and continuing with popular comedy Zware Jongens (1984) and the 1950s nostalgia of Blueberry Hill (1989). He also began making documentaries on the history of Flemish and Dutch cinema.

While his main feature films from the 1980s are available on DVD (assuming you have the patience to rummage through the second-hand bins) De Hert’s earlier work, and that of Fugitive Cinema more broadly, is extremely hard to see. This is where the memorial events this month make their contribution.

On 14 October the Ghent Film Festival will screen Dood van een Sandwichman and De Bom, with producer Willem Thijssen on hand to talk about his collaboration with De Hert, and veteran film journalist Patrick Duynslaegher present to provide context.

A deeper dive into the Fugitive years will then be held at De Cinema in Antwerp on 19-21 October and again on 26-28 October. The programme begins with De Hert’s debut short Twee keer twee ogen (1963), then goes on to cover SOS Fonske, De geboorte en dood van Dirk Vandersteen (1968), Camera Sutra, De Bom, Dood van een Sandwichman, and Le Filet Américain (1981), De Hert’s last film in the Fugitive style.

The Ghent and Antwerp programmes will both be introduced by film historian Gertjan Willems, who has written one of the best appreciations of De Hert’s career. This appears in Dutch on the bilingual film site Sabzian.

Willems has also been instrumental in ensuring that De Hert’s archive is preserved. This covers not just the activities of Fugitive Cinema and his subsequent productions (completed or otherwise) but also the fruit of his obsessional research on Belgian cinema history.

The films have been transferred to the Cinematek for preservation and digitisation, while paper records and other items have been donated to Antwerp University, and will be held in the city’s Felix Archive. From October on, Willems and his colleague Steven Jacobs will organise a seminar to guide Antwerp master students in theatre and film studies through research into the early Fugitive films. The students will also help build an inventory of the archive.

All of this activity would make a lot more sense if the Fugitive films, and De Hert’s other work, were more widely available. Hopefully, we will not have to wait for too long.

text © Ian Mundell 2020

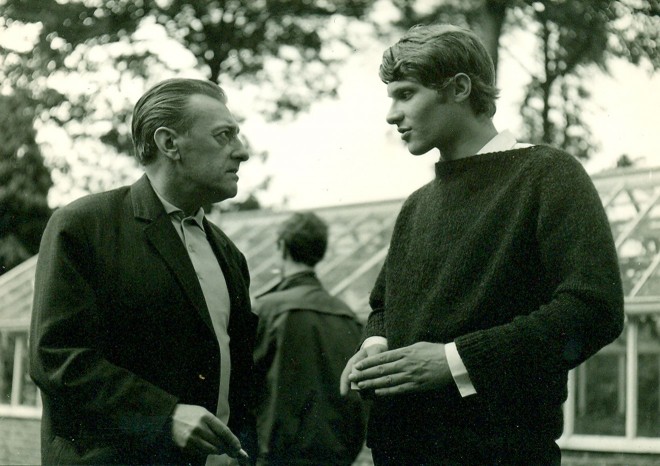

photos courtesy Ghent Film Festival (top) and Antwerp University (bottom)